Do you actually like modern art? Or did the CIA convince you?

Like everything else, art is political.

The idea that the CIA used American Abstract Expressionist art as a Cold War weapon circulated in art circles for decades. After all, how else could a country that dismissed modern art in the 1940s come to embrace it so passionately just a decade later?

For years, the open secret passed quietly through galleries and classrooms, until the fall of the Berlin Wall, when former CIA agents finally confirmed what many had long suspected: that in the years following World War II, the agency—eager to prove America had more to offer than Coca-Cola and capitalism—had quietly launched a covert campaign to export American art, and with it, the values of freedom and self-expression.

The connection between the U.S. government and the art world wasn’t new, however. It had been forged during the Second World War, when New York’s Museum of Modern Art was enlisted to help spread American ideals across North and South America. At the helm was John Hay Whitney, MoMA’s president at the time and a member of the prominent Whitney art family, who firmly believed in art’s power as a diplomatic tool. As he once put it, art “would do more to bring us together as friends than ten years of commercial and political work.”

The Cold War and its cultural demands only intensified this relationship—and the role that art could play in supporting American ideals. Domestically, it had the potential to sway the left-leaning New York art scene; internationally, it could demonstrate the intellectual and creative freedom that could only exist in a democratic, capitalist society.

So why Abstract Expressionism as the weapon of choice?

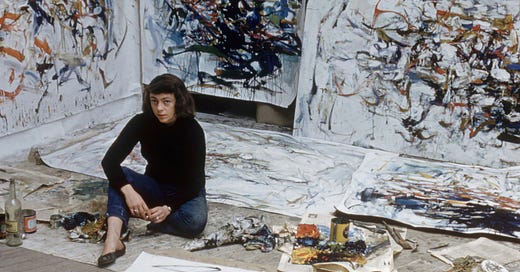

Unlike the art coming out of the Soviet Union, which was stiff, traditional, and rooted in realism, American art was chaotic, expressive, and emotionally raw. It splashed across canvases in splatters and thick washes of emotionally charged color. It was proof, the government argued, that America was not culturally barren or philosophically hollow, as the Soviets claimed. Art, they posited, was about free expression—an idea only reinforced by the number of Americans who initially dismissed modern art as a complete waste of paint. What better symbol of liberty than a country willing to champion art it didn’t even understand?

To avoid speculation and criticism (after all, why would the government fund such “pointless” art?), much of the CIA’s effort to promote Abstract Expressionism was funneled through MoMA. For nearly two decades, the museum tirelessly promoted American art in both New York and in exhibitions abroad, showcasing the works of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and others.

Even more covert was the CIA’s creation of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, a Paris-based organization that appeared grassroots and artist-run, but behind the scenes had Langley’s fingerprints all over it. At its peak, it operated in 35 countries, running magazines, art exhibitions, concerts, and awards programs. It became one of the most ambitious and influential cultural propaganda efforts of the Cold War—until its exposure in 1967. The revelation left many artists and patrons feeling deeply manipulated. Especially considering that many of them, including Pollock himself, held communist and anarchist beliefs. Still, the project had achieved its aims. By the 1970s, Abstract Expressionism hung on museum walls around the world and had recentered the art world from Paris to New York.

Still, it would be a mistake to suggest that Abstract Expressionism was purely a product of political engineering. The movement had already taken root, shaped by a generation of artists grappling with trauma, exile, and existential uncertainty in a rapidly changing world. The CIA didn’t invent Pollock’s drip technique or Rothko’s color fields, they simply amplified them, recognizing their power as cultural weapons. The art itself was already poised for recognition. What the CIA did was accelerate its reach, giving a global stage to a movement that might have arrived there on its own, just more slowly, and perhaps with less intensity.

So, did the CIA make you like modern art? Not exactly. But they may have helped hang it on Europe’s gallery walls a little faster. And if the Cold War had to be fought with canvases instead of coups, maybe that wasn’t such a bad thing. As one curator put it: “I’d much rather the CIA spent money on Abstract Expressionism… than toppling left-wing governments.”

I haven’t stopped thinking about this. I read an article on Jstor about this and honestly nothing has quite broken my matrix quite like this. On days when I feel frustrated as an artist I remember that there are forces much larger and mainly it’s timing, luck and culture

Art as propaganda has been used for centuries by both governments and churches alike.